UPDATE: We are currently writing an article on the 2022 new Food Labeling Regulations for both the USA and Canada. There are major updates, including the Canadian requirement, with an implementation deadline of December 31, 2025, of a front-of-packaging symbol, for any food product containing a high level of fat, sugar or sodium (usually 15% of the daily values of one of these nutrients).

Or is it possibly ahead? An interesting question, isn’t it?

I am in a privileged position. I live in Montreal, but I spend a few months a year in France, where I was born and raised. And I help small food businesses with their US and Canadian food packaging, so, naturally, I am curious to compare European food labels with U.S. or Canadian food labels.

I have also lived in the USA for 10 years where I owned a small food business.

In the USA, nutritional information on food packaging has existed since 1994 and the 2016 new rules were the first major change since its conception. Regulators have learned from 20 years of experience.

In Europe, on the contrary, nutrition facts are only mandatory with the new regulation which came in effect in December 2016. (For products which already had nutritional information, the changes were effective in December 2014).

Regulations on food labels are designed to provide consumers with unbiased, accurate information on what they eat, and help them to make healthy food choices.

At first glance, the approach of both jurisdictions is extremely different, though.

Europe provides consumers with information on a few nutrients, whereas the USA (and Canada) nutrition facts list more nutrients, along with some “tools” to help consumers understand how much they eat and how many calories they get in one serving of food. How many calories are there actually in this pint of Ben & Jerry’s ice-cream you just ate?

So, who got it right?

Let us dig deeper into details of these food labels and let me share some opinions on the decisions European legislators have made vs. what we see in North-America.

Here are the facts about European food packaging and labels, as per the EU legislation, COMPARED with US-Canada labeling:

-

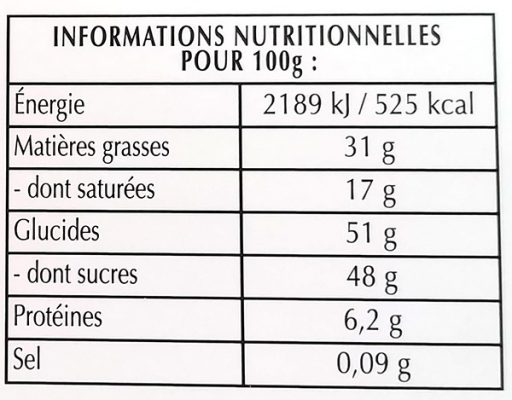

Nutritional information (the table of nutrients):

Mandatory nutrients - The list of nutrients with mandatory declaration is shorter.

- Some nutrients are “optional” but can only be declared if there are present to a significant level (15% of the nutrient reference values for 100 g or 100 ml, or 7.5% for beverages).

- POSITIVE: the label focuses on the few meaningful nutrients, rather than a long list of nutrients.

- The declaration of fiber is optional.

- Not only the mention of cholesterol is not required, but it is not even on the list of nutrients with an optional declaration.

- As you can read in this Harvard article on cholesterol, “Although it remains important to limit the amount of cholesterol you eat, especially if you have diabetes, for most people dietary cholesterol is not as problematic as once believed. The biggest influence on blood cholesterol level is the mix of fats and carbohydrates in your diet—not the amount of cholesterol you eat from food.”

- The only mandatory information is the weight of mandatory nutrients and energy for 100g (or 100ml) of the food. Information per serving or % of reference intakes (daily values) is not required.

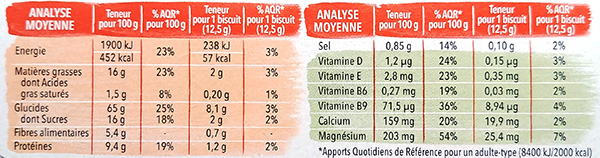

EU Nutrition info with optional nutrients, info per serving size and daily reference intakes - POSITIVE: Consumers can compare the amount of sugar, fat, or carbohydrates for 100 g (100 ml) of any food.

- NEGATIVE: Consumers don’t eat 100 g of any food. A serving of chocolate can be 17 g and a serving of peas can be 130 g. It is much harder for the consumer to know what the calorie intake of a serving of the food is, or if the food is particularly high in sodium, saturated fat or sugar, etc. Personally I like the way Canada has approached the issue. It lists the % of daily values for each nutrient, and, as a footnote to the nutrition facts table, it explains that “5% or less is a little, 15% or more is a lot,” an excellent way to give a sense of perspective to consumers.

- Note: in the European legislation, we talk about (Daily) Reference Intakes (RI) or Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA) to designate what is called daily values in Canada or the USA.

- Interestingly, the word “salt” rather than “sodium” is used here.

- POSITIVE: Salt intake plays a role in hypertension and it is likely that not everyone knows that sodium is salt. The use of the word “salt” makes the information more accessible to all consumers.

- Note: Most of the sodium we ingest is in the form of salt. Salt is sodium chloride (40% sodium, 60% chloride.)

- The word energy is used and is expressed in kJ and kcal.

- NEGATIVE: It is more complicated than the North-American labels which simply say “Calories” followed by the numerical value and no unit of measure.

- Serving size: Food manufacturers have the option to show nutritional information per portion, as long as it is clear to the consumer what a portion of the food is. The portion is indicated by words or a pictogram. However, unlike the U.S. or Canada, there are no established standards for what constitutes a portion of various foods.

- NEGATIVE: It makes it difficult to compare various brands or products. The European Commission is supposed to issue rules “to provide for a uniform basis of comparison for the consumer” for specific types of foods. However, we have not found any recent literature indicating progress on that issue.

- Reference intakes for special populations, such as children: The EU regulation states that “The energy value and the amounts of nutrients can only be expressed as a percentage of reference intakes for adults, in addition to their expression as absolute values.” As the % of reference intakes is not mandatory, we can expect that they are rarely included by manufacturers. In comparison, in the USA, nutrition facts tables are different for infants and children 1-3, and for the latter, the daily values (reference intakes) are based on 1,000 calories per day.

-

Name of food and net quantity:

- It is not required to have the name of the food and the net quantity on the front of the package. Consequently, the weight is often in the back of the package. It makes it more difficult to compare prices because you must grab the product and look in the back to see the weight.

- The requirement is to have the name and the net quantity in the same field of vision.

- One good example is Lindt 70% cacao chocolate bar. In Europe, there is no indication of weight or the word chocolate on the front of the bar, whereas the Canadian product indicates 100 g and the words “dark chocolate.” Interestingly, the US package says “dark chocolate” but not the weight (which it should have!)

Lindt chocolate bar – Name and Net Quantity requirements

- It is not required to have the name of the food and the net quantity on the front of the package. Consequently, the weight is often in the back of the package. It makes it more difficult to compare prices because you must grab the product and look in the back to see the weight.

-

-

- See the complete packages on Amazon:

- Amazon France: Lindt – Excellence Noir 70% 100g

- Amazon Canada: Lindt Excellence 70% 100g

- Amazon US: Lindt Excellence Bar, 70% Cocoa Smooth Dark Chocolate

- See the complete packages on Amazon:

-

-

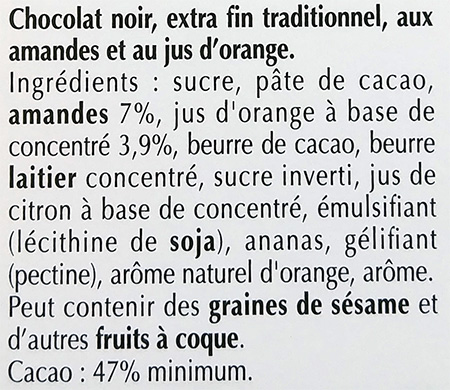

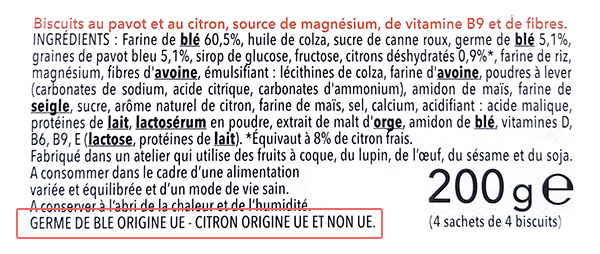

List of ingredients:

Ingredient list with % of ingredients mentioned in the product name and allergens in bold - For complex ingredients, the list of sub-ingredients is not indicated, whereas it is required in U.S. – Canada.

- It is mandatory to mention the % of the total weight for ingredients mentioned in the product name, or in a picture or is essential to characterize the food.

- POSITIVE: It avoids misleading the consumer on the actual make-up of the food. It is rather useful to know that your “duck confit with lentils” jar contains 45% or 15% of duck!

-

Country of origin (COOL):

- A mention of the country of origin is mandatory for certain products, such as meat.

- It is also mandatory when not indicating it would mislead consumers.

- Finally, the country of origin of the primary ingredient must be indicated when there could be confusion on the product’s origin.

Optional mention of country of origin of 2 ingredients - In Europe, we can see in the media that people are particularly eager to know where their food is coming from. This requirement translates the prevalence of such need to know. With such a requirement, Belgian chocolate is suddenly not quite Belgian anymore!

-

Allergen declaration:

- In each of the jurisdictions (USA, Canada, Europe), the list of allergens is slightly different. We can note celery and lupin in the European list of allergens.

-

Legislation implementation date:

- Last, but not least, the approach to implementation is quite different: In the USA and Canada, there is a precise deadline by which all packages need to conform to the new food labeling regulations. In Europe, the regulations state that the current packages can be used “until depletion of the inventory”.

- NEGATIVE: It doesn’t seem particularly easy to control.

- Last, but not least, the approach to implementation is quite different: In the USA and Canada, there is a precise deadline by which all packages need to conform to the new food labeling regulations. In Europe, the regulations state that the current packages can be used “until depletion of the inventory”.

In conclusion, European food labeling provides less information than U.S. and Canadian labeling.

It could be argued that “less is more”.

For instance, the nutrition table clearly focuses on the most important nutrients. However, we can regret the absence of “fiber”. The omission of “cholesterol” is also noticeable, but in the view of the complexity of the science in terms of the impact of cholesterol on health, there must be reasoning behind this omission.

On the other hand, without any mandatory indication of serving size and reference amounts, it is difficult for consumers to make sense of the numbers, only expressed in grams of nutrients for 100 g of food.

It is surprising not to see better nutrition information in Europe, where a number of countries are very health-conscious when it comes to food (Denmark’s consumers buy three times more organic food than the US consumer, Sweden buys twice as much. Seven out of the top 10 countries in terms of consumption of organic food are members of the EU. Source: Statista – Per capita revenues of organic food worldwide.)

It is also surprising when you see that, on the other hand, food packaging gives very detailed information on recycling (in France at least). It describes, for each component of the packaging, whether it is recyclable or not, and even when it is not recyclable, it reminds consumers to “think about recycling”.

How can we explain the focus on recycling vs. nutrition information on food packaging?

I will venture to say that in an “old” Europe where the density of populations is higher than in the great spaces of North-America, recycling is certainly more critical.

And, on the other hand, obesity, diabetes, and other health problems related to food are more severe in America than in Europe, hence the efforts to help consumers understand and influence what they eat. Americans definitely eat larger portions and too much fat and sugar. With nearly 30 million diabetics (almost 11% of American adults), the USA has the highest prevalence of diabetes among all developed countries (Source: Daily Mail).

It remains to be seen if nutritional information on food packages has a positive effect on health. Studies have been made on that topic, and the answer is not as obvious as you may think.

Another topic of interest is the use of Nutri-Scores, shown on the front of packages, and which simply gives a score from A to E to the food, in terms of nutrition and health. The European Commission published a report on that topic in May 2020.

But these are topics for future articles.

To learn more about the new 2016 US and Canada food labeling regulations, read our article: “USA and Canada Food Labeling: 2016 New Regulations”

Reference:

Need some field research for your food products? Need American or Canadian-compliant food labels, compliant with the new 2016 regulations? Feel free to contact us. We can help.

Want to pin this article?